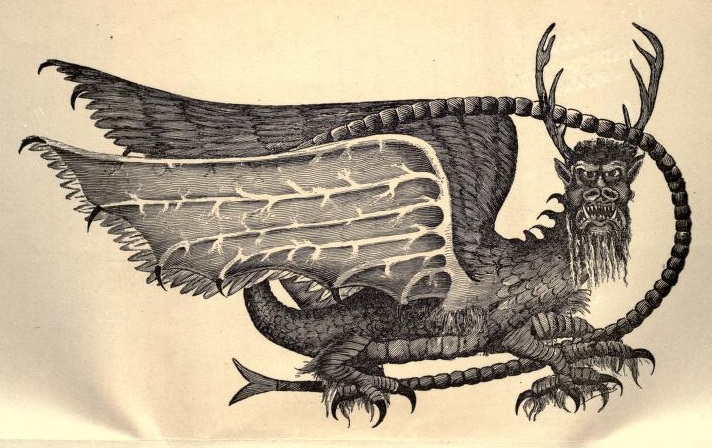

Piasa Bird

unknown illustrator, likely 1870s

(Not representative of the original description of the creature)

Origins:

Sadly, as with most creatures from Indigenous mythology, not much is concretely known, though plenty of hear-say exists.

What can be concretely said about the Piasa Bird (also sometimes called the Piusa) is it was part of multiple murals and rock carvings in Illinois, likely from the prehistoric culture (named Cahokia in the 17th century by the French, after the Cahokia tribe that lived in the area) that resided in the area from roughly 600 to 1350. These artworks included Thunderbirds, snakes, and other mythical creatures, the Piasa Bird appearing multiple times, though not in the form that is now used. It's first description comes from Jesuit missionary Father Jacques Marquette in 1673:

While skirting some rocks, which by their height and length inspired awe, we saw upon one of them two painted monsters which at first made us afraid, and upon which the boldest savages dare not long rest their eyes. they are as large as a calf; they have horns on their heads like those of a deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard like a tiger's, a face somewhat like a man's, a body covered with scales, and so long a tail that it winds all around the body, passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a fish's tail. green, red, and black are the three colors composing the picture. Moreover, these two monsters are so well painted that we cannot believe that any savage is their author; for good painters in France would find it difficult to reach that place conveniently to paint them. Here is approximately the shape of these monsters, as we have faithfully copied it.

This aforementioned image has since been lost, but a map by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin in 1682 does include art as described by Marquette's companion Louis Jolliet:

Of note, it's missing several features now associated with the creature, including its wings. This and the couple of then-contemporary images shows a link between the Piasa "Bird" and the Ojibwe Mishibijiw, also known as the Underwater Panther (the Ojibwe name literally meaning "the Great Lynx"), water monsters that rule opposite the Thunderbirds. They are said to have the head and paws of a large cat, scales covering its body and dagger-like spines along its back and tapered tail (matching Marquette's description quite well). Per Algonquin tradition, the Underwater Panther was the most powerful being of the Underworld, and according to Ojibwe, it controlled all water creatures.

The Piasa Bird is most likely a mid-Mississippi River edition of this mythical beast. It's name comes from a 1778 map by Thomas Hutchkins, in which the area was given the name "Piasas." Where that name came from is not known, but likely is an Anglicisation of a Francization of a local Indigenous word.

But the tale of the Piasa Bird has since grown into a wholly new creature!

By 1699, it's reported that the original murals and carvings of the Piasa Bird were heavily worn, as passing Indigenous Peoples were prone to shooting it. Per "Illionois and the West" (1838), written by Abner Dumont Jones:

The spot became sacred from that time, and no Indian ascended or descended the Father of Waters for many a year without discharging his arrow at the image of the warrior-destroying Bird. After the distribution of fire-arms among the Indians, bullets were substituted for arrows, and even to this day no savage presumes to pass that magic spot without discharging his rifle and raising his shout of triumph. I visited the spor in June (1838) and examined the image, and the ten thousand bullet-marks upon the cliff seems to soroborate the tradition related to me in the neighborhood. So lately as the passage of teh Sac and Fox delegations fown the river on their way to Washington, there was a general discharge of their rifles at the Piasau Bird. On arriving at Alton, they went on short in a body, and proceeded to the bluffs, where they held a solemn war-council, concluding the whole with a splendid war dance, manifesting all the while the most exuberant joy.

Fast forward to 1836, Professor John Russell published a fabricated story that has since taken over as a de facto "truth" about the Piasa Bird (and is in fact the source of it being a bird at all!). As written in "Records of Ancient Races in the Mississippi Valley" (1887), written by William McAdams:

In descending the river to Alton, the reveler will observe, between that town and the mouth of the Illinois, a narrow ravine through which a small stream discharges its waters into the Mississippi. This stream is the Piasa. Its name is Indian, and signifies, in the Illini, 'The bird which devours men.' Near the mouth of this stream, on the smooth and perpendicular face of the bluff, at an elevation which no human art can reach, is cut the figure of an enormous bird, with its wings extended. The animal which the figure represents was called by the Indians the Piasa. From this is derived the name of the stream.

The tradition of the Piasa is stil current among the tribes of the Upper Mississippi, and those who have inhabited the valley of the Illinois, and is briefly this:

Many thousand moons before the arrival of the pale faces, when the great Magalonyx and Mastodon, whose bones are not dug up, were still living in the land of green prairies, there existed a bird of such dimensions that he could easily carry off in his talons a full-grown deer. Having obtained a taste for human felsh, from that time he would prey on nothing else. He was artful as he wa powerful, and would dart suddenly and unexpectedly upon an Indian, bearing him off into one of the caves of the bluff, and devour him. Hundreds of warriors attempted for years to destroy him, but without success. Whole villages were nearly depopulated, and consternation spread through all the tribes of the Illini.

Such was the state of affairs when Ouatogo the great cheif of the Illini, whose fame extended beyond the great lakces, separating himself from the rest of his tribe, fasted in solitude fro the space of a whole moon, prayed to the Great Spirit, the Master of Life, that he would protect his children from the Piasa.

On the last night of the fast, the Great Spirit appeared to Ouatogo in a dream, and directed him to select twenty of his bravest warriors, each armed with a bow and poisoned arrows, and conceal them in a designated spot. Near the place of concealment another warrior was to stand in open view, as a victim for the Piasa, which they must shoot the instant he pounced upon his prey.

When the chief awoke in the morning, he thanked the Great Spirit, and returning to his tribe told them his vision. The warriors were quickly selected and placed in ambush as directed. Ouatogo offered himself as the victim. He was willing to die for his people. Placing himself in open view on the bluffs, he soon saw the Piasa perched on the cliff eying [sic] his prey. The chief drew up his manly form, he bgane the chant the death-song of an Indian warrior. The moment after, the Piasa arose into the air, and swift as the thunderbolt darted down on his victim. Scarcely had the horrid creature reached his prey before every bow was sprung and every arrow was sent quivering to the feather into his body. The Piasa uttered a fearful scream, that sounded far over the opposite side of the river, and expired. Ouatogo was unharmed. Not an errow, not even the talons of the bird, had touched him. The Master of Life, in admiration of Ouatogo's deed, had helpd over him an invisible shield.

There was the wildest rejoicing among the Illini, and the brave chief was carried in triumph to the council house, where it was solemnly agreed that, in memory of the great event in their nation's history, the image of the Piasa should be engraved on the bluff.

Such is the Indian tradition. Of course I cannot vouch for its truth. This much, however, is certain, that the figure of a huge bird, cut in the solid rock, is still there, and at a height that is perfectly inaccessible. How and for what purpose it was made I leave for others to determine. Even at this day an Indian never passes the spot in his canoe without firing his gun at the figure of the Piasa. The marks of the balls on the rock are almost unnumerable.

Russell then goes on to account a personal visit in which he views the sight and climbs the cliff to find a cave full of human bones. Again, from "Records of Ancient Races in the Mississippi Valley":

The strange story in some form or other has had a most extensive circulation. A few years ago after the publication of the tradition of the Piasa, we wrote a letter to Russell. He answered that there was a somewhat similar tradition among the Indians, but he admitted, to use his own words, that the story was "somewhat illustrated." As a mere tradition, the story of the Piasa has little, if any ethnological significance. Cinderella's slipper and Mother Goose's stories tell no more of the unwritten history of Europeans, than the myths of the Onondagas or Tuscaroras do of the origin of the red man.

As for the original artworks, they have long-since been destroyed. Marquette's original report included multiple illustrations of the Piasa Bird being visible on the cliffs, later observations only report on one (likely due to simple erosion). This is corroborated by a illustration in "The Valley of the Mississippi Illustrated: 80 illustrations from nature, by H. Lewis, from the falls of St. Anthony to the Gulf of Mexico" (1839), which depicts one full pictograph and one half-destroyed (interestingly, the full form has wing protusions, though it should be noted that the book details the cliff was well-worn and the carvings quite dim, likely leaving much room of interpretation on the forms):

The worn dimness and bullet damage is mentioned as reasons for the new inclusion of wings, as well as an "atmospheric effect" in which humidity impacts the visibility of distanced items, per "Records of Ancient Races in the Mississippi Valley":

From what we have learned of the great pictograph at Alton, we are satisfied that this atmospheric effect has been the cause, in part, of the Marquette. An old citizen, born and reared almost under the shadow of the bluff on which the picture of the Piasa was, tells me that "sometimes you could see its wings and sometimes you couldn't."

Wings or not, the lone remaining artwork was then destroyed in the 1846-47 as the cliffs were mined for limestone. A reproduction based off the 1880's winged interpretation now exists nearby, firmly planting this "updated" version of the Piasa Bird in the current zietgeist.