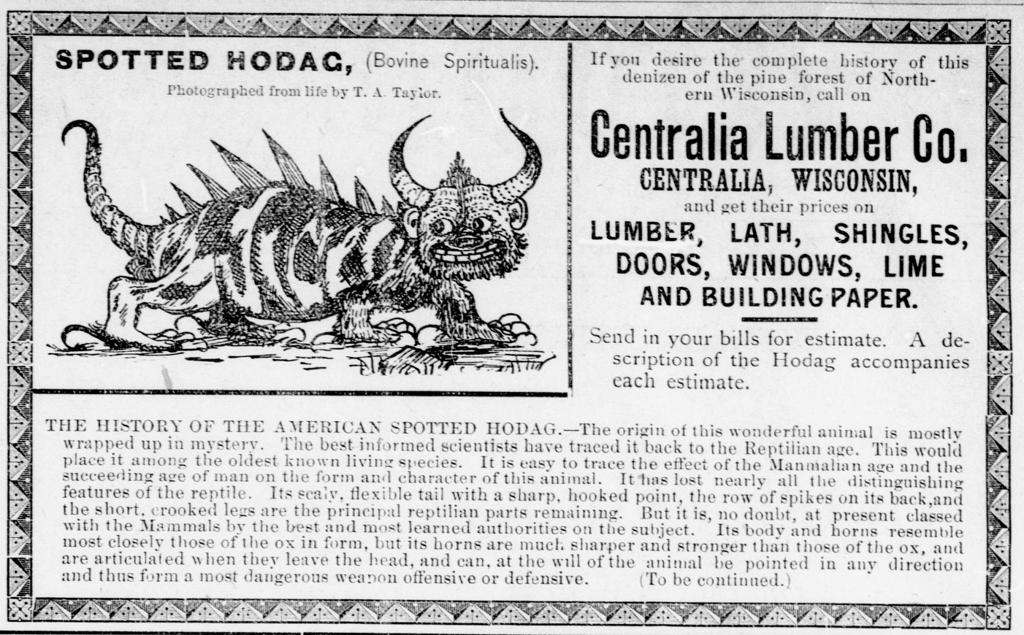

Hodag

illustration by Eugene Simeon Shepard, 1893

Origins:

The word "hodag" can be found in newspapers as far back as the early 1840s, referencing it as the empty litter (e.g. stretcher) pulled by camels. The name is quickly utilized in a new way in a November 16, 1889 article ("That Terrible Hodag Again") in The Arkansaw Traveler, though the title implies it's not a new use:

The oddest and most successful joke that these young duck hunters love to perpetrate, is what is known as "Hunting the Hodag," and woe to the poor lad who is not "on," and is gullible enough to allow himself to be roped into a hodag hunt. This season the victim of the joke was big-hearted Bob Tweedy, and the chances are that he will never hear the last of it.

[...]

"Now, what in thunder is a hodag?" asked the surprised Bob, as he hastily folded up his wealth of limbs, and leaned forward, pricking up his ears the while, like a horse.

"Why," said Dan Brigham, "don't you know what a hodag is?"

"Never heard of such a thing, and haven't the least idea what it looks like," said Bob. "Is it a bird?"

"A bird!" chimed in Rude Richter. "Well that's rich! Nawl it's an animal about the size of a New Foundland dog - sort of a cross between a lynx and bear, (Rude always a good single-handed liar when a joke was on) and it's a fighter from way back. Why, there is old Hinkle over on the other side of the lake, who only last season had twenty cheep killed by a he hodag, and it took twenty dogs to kill it."

Bob was growing more and more excited all the while, and when Rude finished he wiped the perspiration frmo his brow and said:

"By jove, boy, I came up here to hunt ducks, but if there is any bigger game to be had I want a shake at it. Where are you most liable to find these hodags?"

"Well," ventured Will Young, "the hodag is a peculiar animal, and has a special fondness for cornfields. During the day, it sleeps the greater part of the time, except when hungry, and then it grows very bold and can be seen hobering about a sheep fold. At night, however, it loves to prowl about cornfields, and has often been seen dodging about among the tombstones of a graveyard. It seems to love a lonesome place."

Poor Bob eventually catches onto the prank, though only after a full night out.

Hodag, as an animal, returns once more to newspapers in a similar punny context, this time as a sideshow attraction. A November 17, 1889 article ("The Hodag Was Sick: An Explanation by Which an Ex-Showman Escaped a Thrashing") in the Pittsburgh Dispatch details a confrontation between a ex-showman and angry customer on paying a quarter for a non-existant Hodag. No physical description was given (that being the joke in the end). An August 1, 1892 article ("How It Was Played On Dad"), a family is taken in by a sideshow attraction:

"Ladies and Gentlemen, wehave the assurance of no less than five well known naturalists that this ia the only living specimen of the hodag now in existence. He was captured in a hyena trap in South Africa and was brought over here at a cost of $3,000."

It's soon revealed to not be a mysterious animal but instead the very same "crippled hog we sold to the tin peddler."

Finally in autumn of 1893, the Hodag acquired it's recognizable form, reported by Eugene Simeon Shepard near Rhinelander, Wisconsin as a 185 pound, seven-foot long reptilian beast, with a disproportionately large head with horns and fangs. Trimmed black fur covered the stout body with thick spikes along its spine and down its tail. It also had quite the foul oder, which Shepard described as a "combination of buzzard meat and skunk perfume."

Returning to Rhinelander, he collected a hunting band, and together they killed the beast. Subsequent hunts in 1896 and 1899 followed, the latter commemorated with photos (the second with Shepard's own handwritten note).

Of course, as with the prior reports, this was meant wholly in good fun, a wink of entertainment.

The hodag would later be given new meanings, such as in J.E. Rockwell's Some Lumberjack Myths (1910):

The “Hodag” was a monster of hideous mien, a re incarnation of the spirit of the lost ox. In Paul Bunyan’s days horses were not used in the lumber camps. Oxen were the beasts of burden in the woods. Once in a while one would wander away and never be seen again. The lost oxen, according to the lumberjacks, turned into Hodags, and became as wild and terrible as they were formerly tame and peaceable. Their cry was something to make the stroutest heart quake. Not many years ago “Gene” Shepherd, the famous Wisconsin woodsman joker, hoaxed the whole scientific world with a photograph of a Hodag, caught in his lair. Among other things Gene had learned taxidermy, and at some expense and no end of labor, he transformed a peculiarly shaped log into as ferocious an animal in appearance as ever a Jack saw in his wildest nightmare.